Culturetracker works towards changing safety behaviour through the application of management processes. The company provides services to measure safety culture via surveying people’s attitudes towards safety, as well as a consultancy service which works with companies to help them deliver effective processes in areas including communications, development, leadership and benchmarking, in order to support the implementation of a positive safety culture.

Richard Barnes, Culturetracker's Managing Director, comments on the topic of positive health and safety culture.

HLS: Could you explain to us what is a positive safety culture?

Richard Barnes: I think ultimately a positive safety culture is one where everybody in the organisation from top to bottom has a daily focus on safety and risk in the jobs that they do, or in the situations that they come across, within the environments they work in. It’s about a plan to create a company in which everyone is safety conscious and that involves many different things in terms of establishing that culture. It starts with the leadership of the organisation. If the culture isn’t there, then it won’t be anywhere else in the company and people won't be aware of it.

Obviously in this day and age we have much more litigation on safety, so even though directors have always had considerable responsibilities for health and safety duties, the extent to which they perhaps have paid attention to them has not been as great as it tends to be now. Particularly, the level of sentencing in the new Sentencing Guidelines that are coming into play at the moment will very significantly raise the risks of a health and safety breach from a financial point of view with companies. The issue of corporate liability and people going to jail hasn’t really presented itself as a big threat in the Corporate Homicide Act as it might have done. I think for many companies the real risk of major financial impact on the business plus the ability of HSE to charge for their time now, has made that threat become more of a reality at director level.

The other side of things for the leadership of the organisation is what they can do with the publicity arising from a very effective safety culture. That is something which in construction in particular has become a big selling point for organisations. In recent years major road building projects like the Crossrail Tunnel and the Olympics Stadium has gone to organisations who have a very good safety track record and they are able to promote that. Their safety track record is part of the offering they make to clients and is associated with a premium value on the bids that they make. So, I think that also influences leadership attitudes.

Once you get beyond that, then it really becomes a case of trying to get that safety consciousness down into the rest of the organisation and that has to include all levels of leadership. That can be leadership in terms of trade unions, supervisors, team leaders or anyone who has an influence over other people. So, perhaps it’s better when talking about leadership to talk about influencers rather than leaders, because an influencer could be a long-serving employee who could be seen as being the expert or the person to go to if someone has an issue.

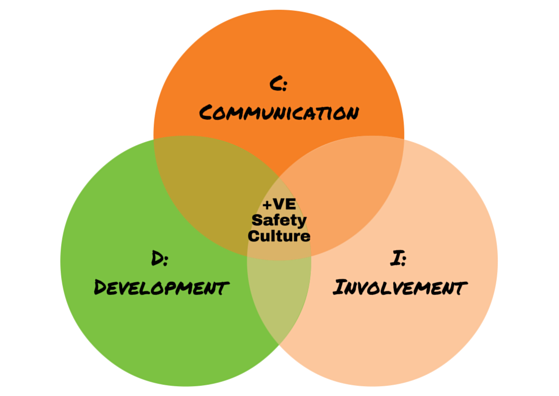

Also, you need to develop a culture which has a combination of what I call the CID approach, Communication, Involvement and Development. There has to be a constant flow of information about safety issues, whether that’s something as simple as changing posters on the walls to issuing safety notices, to including safety as a regular part of toolbox talks, team briefings, or other kinds of interactions with employees. It’s also about senior managers being visible on the shop floors occasionally, involving people in safety issues themselves and talking to people as they walk around the site. Those kind of informal elements of communication and involvement are also important.

And thirdly, you have your D which is development and making sure that you have a well-established process of regular training and refresher routines for safety issues within the organisation. You need to back that up with measurement, e.g. analysis of accidents or feedback from near miss reports and benchmark yourself against other organisations with superior safety records, which might include becoming a member of the British Safety Council or similar bodies. If you can create a structure and a series of processes within the organisation and encapsulate all of those elements, then you are 95% there towards establishing a really solid safety culture. Sadly, what happens in many cases is that a lot of these initiatives are little more than fads; they work for a while and then they disappear.

HLS: Why does this happen?

RB: I think, often it’s because of change of ownership, or because the person driving the particular process has left and someone else sees things differently, but the real reason why it happens is because one senior manager thinks they’ve done their bit and they tend to leave it to people at lower levels of the organisation to drive those processes without managing and monitoring them. So, senior management involvement in the measurement, analysis and benchmarking process is absolutely critical. Senior managers need to have clear KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) on health and safety, which could include things like the frequency of health and safety committee meetings. They could also include measuring near miss reports coming in, accident statistics, reports from external parties, reports from inspections, etc.

HLS: You mentioned earlier the new Sentencing Guidelines and the fact that the law is getting more strict and penalties are getting higher. Do you think this is a good driver for managers to change their safety culture?

RB: Obviously, if you have people that are already committed to health and safety, you’re half way there to establishing the safety culture anyway, but it is a sad fact that an awful lot of people in middle management particularly, the ones that have to “get the job done”, often don’t see safety risks in the same light as perhaps they need to. Therefore, managers at the very senior levels tend to never hear about it and don’t necessarily make an intervention until something goes wrong. That’s the reason why many organisations have fairly poor safety cultures. Ideally, we should be recruiting people that have that safety mentality to start with, but in reality the situation is that that just doesn’t happen.

The problem with safety is that it’s an invisible element. You can look at somebody’s university degree and see what they’ve got, you can assess their performance, but with safety you’re very much trying to measure something which doesn’t happen, as opposed to something which does. Ultimately safety culture is built on prevention and you can’t see prevention; you can see an accident, but you can’t see the prevention of an accident. You have to have a mind-set which thinks beyond the immediate sensory input that you’re receiving about the environment and visualise the risk of what might happen, but again might not. I think that kind of mentality isn’t necessarily the norm when it comes to someone whose pressures on a day to day basis are to get 10,000 units out or to get off site by five o’clock.

HLS: Is this a mentality that you could develop or do you need to hire someone who already has it?

RB: I think both of those things are true. You can develop it by exposing people to scenarios of what happens when these things do go wrong. Sometimes just the shock factor of seeing what can happen when an accident occurs can be enough to make people think, 'well, that could happen here and maybe we should be doing something about it.'

HLS: Do you think using this shock factor is effective?

RB: It can be, it’s like all forms of training and development, it depends on the person that you’re delivering the training to. There’s quality in the training, but there is also the reception. You can throw lots of money at people and some still won’t change, because they have a 'health and safety gone mad' mentality in their heads and see everything as a blockage to what they want to do as opposed to something that maybe is saving lives, saving people from serious injury and creating a higher morale among the workforce. So, you have to accept that some people you may have to let go. But the vast majority, I think, providing that you have the leadership from the top on safety, will change. But a good safety culture has to have constant drive from director level in the business.

HLS: How do you convince those biased members of staff or managers that safety culture is important and is necessary?

RB: Well, I think that starts with the induction and choice of people at recruitment, obviously, and it goes on to giving managers targets and other measures of performance that relate to safety. Again, that can ensure that your measurement and analysis is getting back to you. For example, if you have six managers managing different, but equally hazardous aspects of work, and two or three of them are putting in very few near miss reports or don’t cover many safety issues when they do their briefings, then you’d be able to identify that from your own measures at the top level. So, again people measurement comes in and senior managers being able to find a way of getting a handle on what’s going on lower down in the organisation.

HLS: Why is safety culture important and how can it change a company?

RB: I think the biggest issue is the support it gets from employees. Most employees, although they may have no supervisory responsibilities, do feel that safety is an issue that is part of their day to day concerns. You get some that don’t, but the vast majority of people are concerned about their own health and safety and therefore having a positive safety culture has an impact on where motivation and loyalty to the organisation lies. This is shown to be one of the most important elements of a good positive culture, not just safety culture, but a culture of high performance and commitment to the job. If that safety culture isn’t there that can significantly affect whether people care or believe in or trust the management of a company. So, I think there is an element in that and as I said earlier on, I think there are significant gains for any business to promote their safety performance as part of their PR, and particularly if they’re selling products that have safety features embedded in them.

HLS: Could you explain to us what does behavioural safety mean?

RB: Behavioural safety, really, is what one might call risk awareness. Behavioural safety starts with what people think and again it goes back to the people’s ability to see beyond just what’s immediately in front of them or what they’re intending to do. It's about people recognising and being able to see risk. If you show two people a picture of the shop floor, one of them will find 20-30 risks that they can easily spot, the other will see none at all. So, people’s ability to see risk differs from person to person. The first thing you have to do is to make sure you have significant levels of training and induction in health and safety risk and how to spot risk and deal with it when you see it.

You also need to make sure that behavioural safety is followed and encouraged by the people that supervise everyone. You don’t want a situation where people are discouraged from reporting near misses or safety issues by supervisors and that can certainly happen. Supervisors sometimes can see that as a criticism towards themselves and they don’t want people reporting health and safety risks in their area, because it might come back on them.

So, first you need to train everybody in basic risk awareness; that’s the start of a safety culture. Then you need to back it up with different programmes of safety improvement around the site. For instance, housekeeping inspections where people conduct their own little inspections of their work areas and become more safety conscious that way. You can run programmes like the Japanese 5S (Sort, Streamline, Shine, Standardize and Sustain) approach which combines efficiency with safety and a clean tidy work environment. Those kind of systems can work very effectively, especially if they are renewed every so often in order to create a bit of competition on safety between groups.

Finally, rewarding good safety behaviour. It’s very easy to reward people for getting 15 new sales, it’s less easy to reward somebody for not causing an accident to happen, because again you can’t see it; you can’t see the fact that they have done something to prevent an issue, by taking care or by asking the question. So, managers and supervisors have to become very aware of the opportunity just to thank somebody for bringing something to someone’s attention or for keeping a neat and tidy work area, or for displaying behaviour which positively supports safety. Those kind of people maybe were criticized in the past for being slower than others, because they are a bit more careful when setting up a piece of equipment before they do a job. On the contrary, that kind of behaviour needs to be positively reinforced.

HLS: Which are the main challenges when you’re trying to convince someone that they need to change their safety culture?

RB: I think the main challenge is still that kind of ‘it’s not going to happen to me’ mind set and not being able to see risk, but again, I think this is something that people can be trained to see. I don’t think that’s a blockage, it’s a challenge in the sense that it can be hard work sometimes to get people to see where risk can lie. But my experience is that usually when you sit people in a room, 90% plus will actively engage in analysing risk and will bring lots of matters to your attention that they are aware of. It’s simply the case of giving people the space to bring those kind of issues up.

The bigger problem is when you’ve got someone in a significant leadership role, whether that’s a manager or a director, or someone who is perhaps a very experienced operator or engineer, and if they have a very anti-health and safety mentality then they can undo an awful lot of good work and they can become very counter-culture. That again goes back to the senior management not tolerating that and making sure that part of their performance reviews clearly focuses on the health and safety message and how well they get it across to people. In most cases it’s blindingly obvious who these people are, you don’t need a degree in psychology to work it out, you just need to go and talk to a few people and listen to what you’re hearing and see people’s behaviour, so it’s far from being impossible to tackle. It’s just that quite often these people are in positions of influence, experience or longevity in an organisation and they can quite obviously be difficult to work with and as a result sometimes people back off tackling them when maybe they need to be taking them on further down the line.

HLS: If a company is ready to change their safety culture, what is the first step they need to make and how long does it take for the safety culture to change?

RB: The first step is the statement of intent by senior management. Most companies have a health and safety policy, well, all companies should have a health and safety policy by law, but not very many companies have a formal health and safety improvement policy. That is the first step. Senior management needs to define exactly what the changes in behaviour and in the processes that will drive that behaviour need to be. There has to be a clear strategic approach set at the top of the organisation to what they want to change. What you then have to do is to refine the processes, procedures, measurements to intervention, etc. that will help you deliver that changed culture.

The length of time it takes to some extent is one of those long pieces of string, it depends on the size of the business. If you’re the National Health Service, changing their culture has been attempted by a number of governments over probably the last 50 years without an awful lot of success. So, changing an organisation as big as that is going to take decades. A business with 100 and odd people in it should be able to change their culture significantly within the space of 12 months. As long as you have processes in place to sustain that change and leaders who aren't just paying lip service to it.

One of the problems with most change is that it’s elastic and if you push that piece of elastic you move it, but if you back off and you stop pushing then the elastic just returns back to its previous position or close to its previous position. So, to change culture permanently you will have to make sure that your mindsets and processes are changed permanently and that means drilling down to recruitment processes. You start by selecting the right people right at the start of maintaining that culture. In this case culture can change within a year, but also you can just as easily allow it to change back again within six months, unless you maintain pressure.

.png)